EARTHQUAKE IN THE REGION AIQUILE AND TOTORA

BY

CRISTINA CONDORI

ABSTRACT

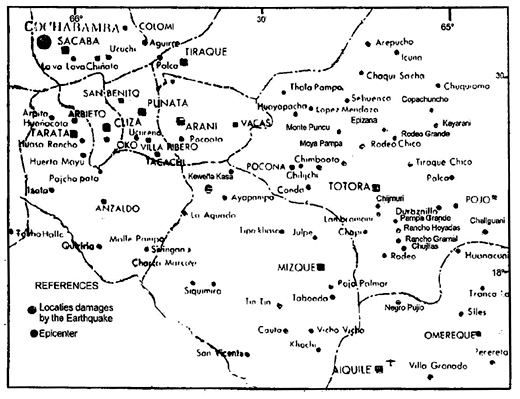

Owing to its little seismic activity, Bolivia (Fig. 1) is not a country prepared to withstand a strong earthquake. The seismic history reports ten strong earthquakes that caused casualties and minor damage. Therefore the population is not prepared to withstand, much less confront, a destroying earthquake. An example of this is the earthquake on 22 May 1998 occurred at 00:48:50 (GMT), magnitude, MI 6.6 and Mw 6.8. It caused damage in several small town and countries of Mizque, Campero and Carrasco Provinces of Cochabamba Departmentin (Fig.2 and Fig.3). This strong earthquake had four foreshock; according the seismic record, at 00:25:46 , 01:36:15 , 04:25:06 and) 4:35:42 universal time GMT, with magnitudes 2.7 to 5.8. The San Calixto Observatory report the prelimanary epicenter location at distances of 16 km to northwest of Totota, 35km and 50km to northeast of Mizque and Aiquile and depth of 13km (Fig.4).

The aftershocks followed without any interruption until to may 27, this day the movement stop for one or after that the activity continued up to now (1998-08- 28), the amount reaches 2370 aftershocks. When one big earthquakes occurs the adjustment process produces (in general) an exponential decreasing in the number of aftershocks with time, but in our case this is not totally true (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). The aftershocks are caused by the barrier and/o the asperities due to the heterogeneous material presents in or around the fault plane, where the main rupture occurred.

The macroseismic and geological effect probe that the epicenter is not located in or around Aiquile or Totora faults. The causes of damages in Totora was the age and instability of the houses: the main the unconsolidated sediments on the ground. In both communities the Intensity was VII MM. The big damage was concentrated in the countries of Rancho Hoyadas y Pampa Grande where the maximun intensity was VIII MM.

Through the intensities the macroseismic epicenter was located at longitude of 65.160o W and latitude 17.850o S, and 11km depth; the epicentral area, that main instrumental epicenter, will be between Pampa Grande, Hoyadas and Huerta Loma countries at depths 10 to 20 km. The difficulty to find a more precise epicenter is because de variation in the crustal thickness below the seismic network of Observatorio San Calixto. This anomaly is obtained in the arrival time of first phase. This problem is analyzing now. The main rupture should be a NWW-SEE strike slip located at depth between 8 km to 20 km.

The evidence observed in 25 communities in the disaster zone shows more destruction to the east of the epicenter; the communities most affected are those of Aiquile, Pampa Grande ( Cochabamba ) and Rancho Hoyadas.

The emanation of water in several places in the disaster zone constitutes further observed evidence: these emanations have an approximately N-S orientation and they appear to be the product of underground readjustment due to the continuous seismic movement.

INTRODUCTION

The frequency of strong motion in Bolivia is low in comparison with that of neighboring countries mainly Chile and Peru . However, the historical (see Table 1 (1,2)) and instrumental earthquakes indicate that in Bolivia earthquakes have occurred and that they have caused casualties and considerable material damage (1).

The data of Table 1 are evidence of the occurrence of earlier earthquakes in the zone where the recent earthquake of 22 May 1998 occurred. The first reference to a strong earthquake felt in Aiquile is on 25 October 1925 , with a magnitude of 5.2 and an intensity of IV. However, there is no specific report either of casualties or of damage. The second reference to a strong earthquake felt in the Aiquile zone is on 1 September 1958: it caused collapse and cracks in old constructions; as with the first one, there is no report of casualties; the magnitude was calculated to be 5.9 and the intensity was calculated to be VI-VII; several constructions with cracks remained standing and were repaired in order for them to be inhabited. A third earthquake is reported in the Aiquile zone; it occurred on 22 February 1976 , with a magnitude of 5.2 and an intensity of V-VI; it caused fissures in the brick constructions (Fig. 7).

All those references confirm that the Aiquile-Totora region is a hazard zone.

FIELD REPORT

We have visited 25 locations (see Table 2, Fig.2), because there were damage reports from communities and news about emanations of water. Also, these communities are located near to the epicenter obtained by Observatorio San Calixto, the national seismological center of Bolivia .

The following is a list of our observations of the disaster zone.

In the town of Punata , the earthquakes were felt and caused some cracking.

In the community of Arani, the earthquakes were felt; our group heard no reports of damage to dwellings.

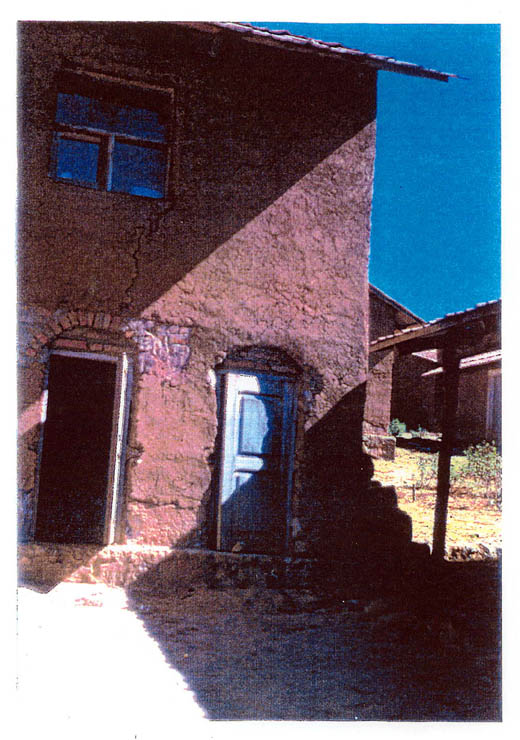

In the settlement of Keweña Kasa, our group observed cracks in walls and in brick floors. Most of the dwellings had been evacuated. We observed some fissures in the upper structure of Puente Mizque (bridge).

In the town of Mizque , some structures suffered considerable cracks in walls and floors, especially the alcaldía building (council) and the church, both structures being rather ancient. Other serious damage was the fall of the roof of a house and smaller losses were minor cracks in most of the dwellings. We did not observe ground fissures.

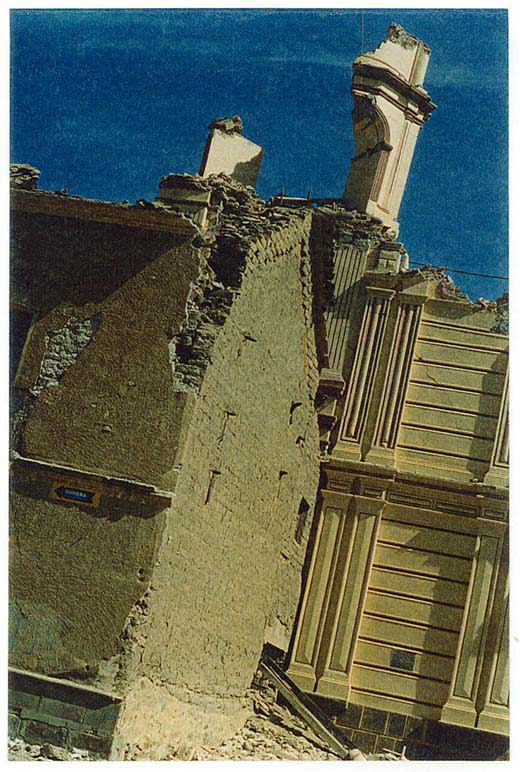

In the town Aiquile, 46 percent (3) of the houses were left uninhabitable, 29 percent were variously damaged and affected by cracks and 25 percent did not show any damage. This indicates that the variation of soil type in Aiquile was an important factor contributing to the degree of construction damage. Our group did not find any ground cracks or water emanation.

Beginning with the community of Pujio Negro, our group began to observe ground fissures: construction damage continued.

In the community of Chujllas, in the central region between Aiquile and Totora, our group found construction damage and ground fissures of increasing extent. Moreover, we found ground water emanation, which was probably caused by seismic movement opening fissures for ground water escape.

In Rancho Gramal, the damage was to constructions, with cracks in the walls of the houses. This community included the settlements of San Gerónimo and Cerro Carreras, were we found small cracking in the dwellings and landslips along río Mizque.

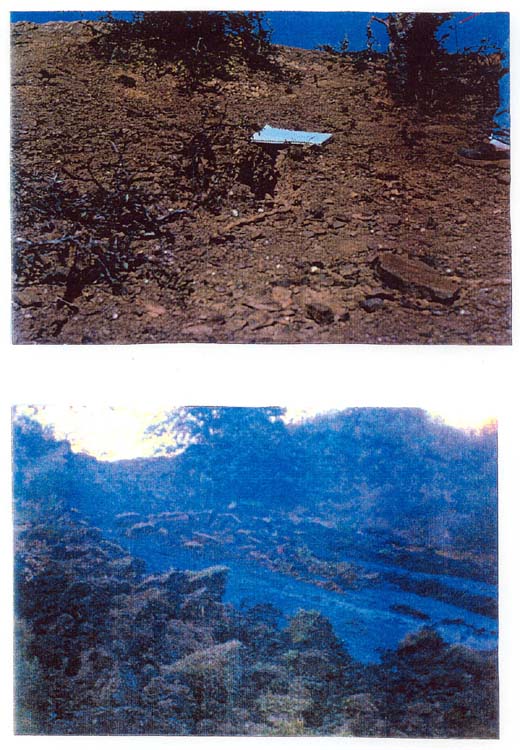

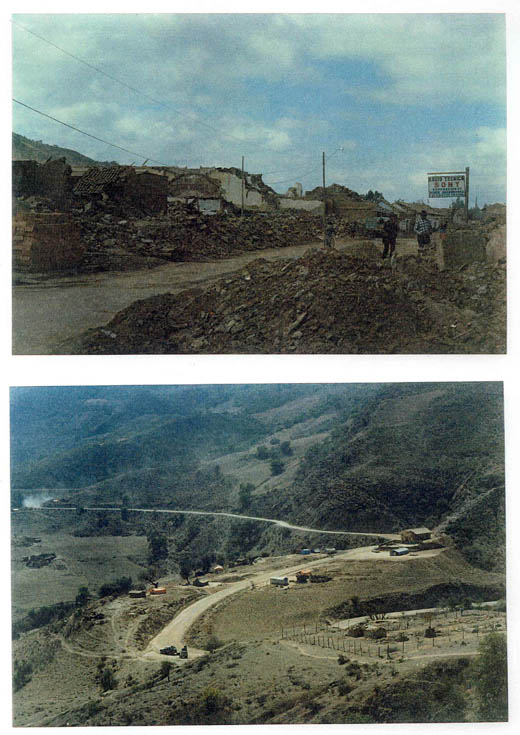

Rancho Hoyadas was made up of fifty houses, all of which were destroyed by the main earthquake. We found figures of width approximately 20cm and of depth approximately 1.7 m. In Rancho Hoyadas we felt an aftershock and we could see dust, caused by the sliding of unconsolidated material, along the cliffs.

In Corral Viejo, our group observed and some cracks slopes some fissures in the slopes.

In Pampa Grande, our group observed cracks of verying depths and widths.

In Lambramani, construction damage was to 28 dwellings and there were soil fissures. Two people were injured as a result of falling roof blocks and wall sections. We noted that construction appeared to be rather precarious.

In Chijmuri, there was damage to construction as a result of wall cracks; also one person was injured as a the result of the fall of part of the roof; there was ground water emanation, probably as a result of fissures caused by vibration from the earthquakes.

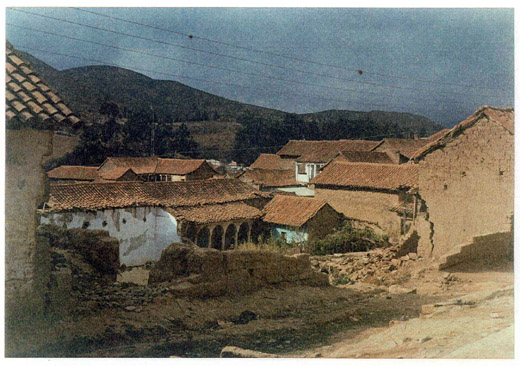

In Totora, 70 percent of the houses were affected. Here we were able to see clearly that one of the causes was the age of the structures; the settlement was founded in 1850 and, in its central part, the ground soil is unconsolidated sediments.

In the region of the community of Escuela de Moya Pampas , we observed the greatest emanation of ground water; it had a dark color, apparently from organic material in the soil. Also, we observed soil elevation of width approximately 5 m, caused by water saturation and continuous earthquake vibration movement.

In Epizana, there were small cracks in the structures; we experienced small movements repeatedly.

In Rodeo Chico, the dwellings were slightly damaged; there was fissuring by extension, accompanied by surface ground water.

In Rodeo Grande, one houses was seriously damaged and one person was injured as a result of failing blocks.

In Tiraque Chico the school and the church tower were seriously damaged; one house collapsed and there were small cracks n several houses; the bridge at the entrance of the settlement showed cracks in its upper part.

In Copachuncho, there were small cracks in the dwellings, but none in the ground.

In Kayarani Zone, there were fissures in the ground and cracks in the school and several dwellings.

In Pojo, we saw no damage.

In Cochabamba , one house collapsed in Villa Tunari calle Chapare. This collapse was due to the design to the design of the structure, which did not withstand only a small movement.

In Llavini, on the Cochabamba-Oruro road, we did not see Structural damage.

CONCLUSIONS

In a preliminary analysis, we determined that:

The damage was produced in the houses located in the central part of Aiquile, confirming that the cause was the variation of the type of soil where the houses were situated.

The damage was accentuated in the area understood between Rancho Hoyadas and Parnpa Grande, mentioned above. It was shown by the severe damage of the 100 percent of the dwellings and for the presence of cracks with a maximun width of 25 cm a depth of 2 m and an extension 100 m. This region is approximately 28 km to the southwest of the epicenter.

The emanations of water are the result of the constant seismic movements due to the readjustment of the ground and due to the cracking of the rock through which the underground water filters.

Fig.2

Fig.3

Provincias y Comunidades Afectadas por El Sismo del 28 de Mayo, 1998

Fig.4

Pic.1 Kewena Kasa

Pic.2 Aiquile

Pic.3 Rancho Hoyadas Moya Pampa

Pic.4 Aiquile Rancho Hoyadas

Pic.5 Pampa Grande

Pic.6 Totora

| Date | Magnitude | Intensity | Localidade | |

| 1650-Nov-10 | 6.4 | VIII | Sucre (Alto Perú) | |

| 1845-Jan-14 | 5.2 | VI | Santa Cruz. | |

| 1851-Jul-05 | 5.4 | VII | Daños en Potosí | |

| 1877-May-17 | 5.4 | VII | Consata. | |

| 1884-Nov-26 | 6.8 | VII | Tarabuco, Sucre | |

| 1887-Sep-23 | 6.8 | VIII | Yacuiba | |

| 1891-Aug-15 | 5.9 | VII | Consata | |

| 1899-Mar-23 | 6.9 | IX | Yacuiba | |

| 1909-May-17 | 6.1 | VIII | Tupiza | |

| 1909-Jul-23 | 5.2 | VI | Sipe Sipe | |

| 1923-Sep-02 | 6.1 | III | Mapiri y Consata | |

| 1925-Qct-25 | 5.2 | VI | Aiquile | |

| 1929-Feb-19 | 5.3 | III | Warnes Santa Cruz | |

| 1932-Dec-25 | 5.2 | VI | Colquechaca Potosi | |

| 1937-Nov-03 | 5.4 | IV | Consata | |

| 1942-Dec-25 | 5.2 | VI | Cochabamba | |

| 1943-Feb-18 | 5.2 | VI | Cochabamba | |

| 1947-Feb-24 | 6.4 | VIII | Consata Mapiri | |

| 1948-Mar-28 | 6.1 | VII | Yotala Sucre | |

| 1949-Nov-07 | 4.6 | VI | Florida Sta. Cruz | |

| 1956-Aug-23 | 5.8 | VI | Consata | |

| 1957-Aug-26 | 6.1 | VII | Postervalle | |

| 1958-Jan-06 | 5.2 | VI | Pasorapa Cochabamba. | |

| 1958-Sep-01 | 5.9 | VII | Destrozos Aiquile | |

| 1970-Mar-06 | 4.6 | VI | Tinquipaya Potosi | |

| 1972-May-12 | 5.0 | VII | Quillacollo Cochabamba. | |

| 1976-Feb-22 | 5.2 | VII | Quiroga y Aiquile | |

| 1976-Jun-30 | 4.7 | V | Arque | |

| 1981-Apr-05 | 4.3 | IV | Tinquipaya | |

| 1981-Jul-23 | 4.9 | VII | Ivirizagama | |

| 1982-Aug-23 | 4.4 | V | Oruro | |

| 1983-My-10 | 4.3 | IV | Node de Potosi | |

| 1983-Sep-05 | 4.0 | III | Sacaca | |

| 1984-Jun-27 | 4.6 | Sabaya Oruro | ||

| 1985-Mar-19 | 5.2 | III | Monteagudo | |

| 1985-Oct-27 | 4.4 | II | Yanacachi La Paz | |

| 1986-Mar-20 | 4.9 | V | Chapare Cochabarnba. | |

| 1986-May-09 | 5.5 | IV | Villa Tunari | |

| 1986-Jun-19 | 5.1 | IV | Villa Tunari | |

| 1987-Aug-31 | 4.7 | III | Foresta Santa Cruz | |

| 1988-Apr-27 | 4.9 | Postervalle | ||

| 1988-Sep-20 | 4.8 | III | Postervalle | |

| 1991-Jun-21 | 3.8 | IV | Cochabamba | |

| 1991-Dec-21 | 5.0 | Berrnejo Yacuiba | ||

| 1992-Feb-13 | 3.0 | III | Cochabaniba | |

| 1994-Jun-09 | 8.3 | V | La Paz | |

| 1997-Oct-17 | 3.9 | III | Sucre | |

| 1998-May-22 | 6.8 | Aiquile Totora | ||

| EPICENTRO | 17°45.600' | 64°55.980' | ||||||||

| Punata | 17°37.800' | 65°49.980' | ||||||||

| Arani | 17°34.020' | 65°46,032' | ||||||||

| Kewña Khasa | 17°40.080' | 65°38,120' | ||||||||

| Mizque | 17°56.251' | 65°18.750' | ||||||||

| Aiquile | 18°11.886' | 65°10.735' | ||||||||

| Negro Pujio | 18°03.929' | 65°09.034' | ||||||||

| Chujllas | 17°59.403' | 65°08.166' | ||||||||

| Rancho Gramal | 17°58.211' | 65°08.643' | ||||||||

| San Gerónimo | 17°57.479 | 65°09.758' | ||||||||

| Cerro Carreras | 17°58.231' | 65°09.122' | ||||||||

| Rancho Hoyadas | 17°55.311' | 65°10.106' | ||||||||

| Corral Viejo | 17°54.688 | 65°09.353' | ||||||||

| Rumi Khasa | 17°53.143 | 65°09.641' | ||||||||

| Pampa Grande | 17°50.948' | 65°10.193' | ||||||||

| Lamabramani | 17°47.344' | 65°11.814' | ||||||||

| Chijmuri | 17°45.420' | 65°12.335' | ||||||||

| Totora | 17°43.875' | 65°11.438' | ||||||||

| Escuela Moya Pampa | 17°40.867' | 65°12.596' | ||||||||

| Epizaria | 17°38.000' | 65°13.682' | ||||||||

| Rodeo Chico | 17°38.324' | 65°11.003' | ||||||||

| Rodeo Gande | 17°39.105' | 65°07,676' | ||||||||

| Tiraque Chico | 17°39.864' | 65°05.617' | ||||||||

| Copachuncho | 17°32.756' | 65°05.270' | ||||||||

| Kayarani zone | 17°35.881' | 65°03.880' | ||||||||

| Pojo | 17°54.000' | 64°52.000' | ||||||||

| Cochabarnba | 17°14.400' | 66°05.400' | ||||||||

| REFERENCES | ||||||||||

| 1. Vega, A. "Historia Sísmica de Bolivia" (in press). | ||||||||||

| 2. Ayala, R. "Atenuación de las intensidades sísmicas en la Cordillera de los Andes Centrales, Bolivia". Revista Geofisica #40, 183-199, 1994 | ||||||||||

| 3. Peñaranda, R. "Terremoto, la noche rnas larga". Santa Cruz, Bolivia, 1998. | ||||||||||

Data source (Country report)

1. Name: Salome Cristina Condori MACHACA

2. Organization: Geologist, Observator San Calixto

3. Course: 1998-99 S

4. Title: SEISMIC OBSERVATION IN ARGENTINA